Environmental Considerations of a Carwash Next to Rio Ayampe

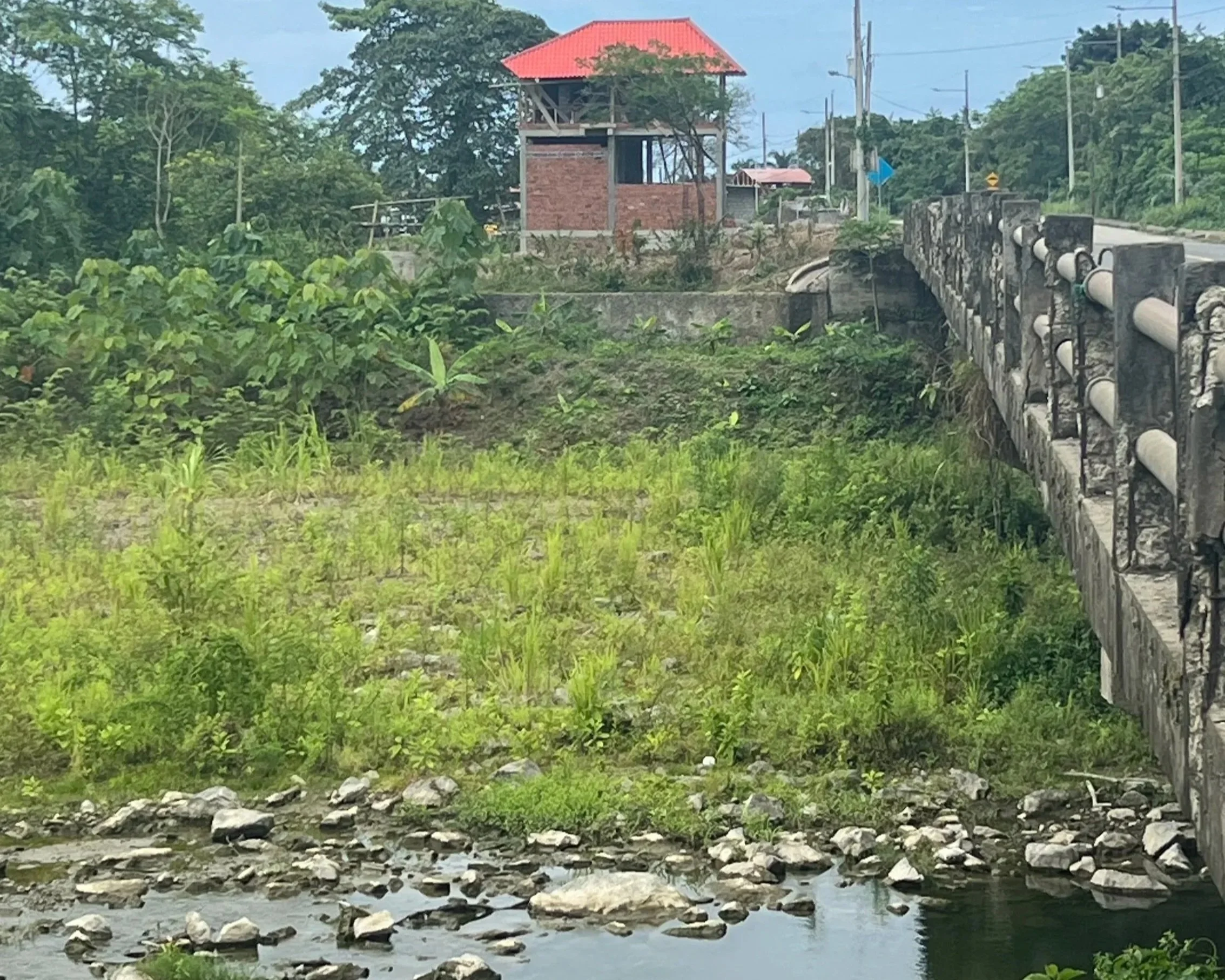

View of the building under construction nect to Rio Ayampe

A carwash is being built next to Rio Ayampe in Ayampe, a small coastal watershed that drains directly into an estuarine system. From a hydrological and water quality perspective, the proximity of this type of operation to the river warrants careful evaluation.

Carwash wastewater typically contains petroleum hydrocarbons, detergents and surfactants, suspended solids, and dissolved trace metals such as zinc, nickel, chromium, and lead. Surfactants increase the mobility of hydrocarbons and metals, allowing them to remain dissolved and travel farther through water and soils. Heavy metals do not degrade and can accumulate in sediments, groundwater, and aquatic organisms.

Once introduced into the environment, these contaminants can move through surface runoff, shallow groundwater, or subsurface flow paths, eventually reaching the river and downstream estuary. Their effects are often chronic and cumulative rather than immediately visible.

Treatment limitations and human health risks

Effective treatment of carwash wastewater generally requires multiple stages, including sedimentation, filtration, and adsorption processes. Basic grease traps or simple filtration systems are not designed to remove dissolved surfactants or heavy metals.

In small commercial facilities, treatment efficiency depends heavily on system design, maintenance, and consistent operation. Even where treatment infrastructure exists, performance can fluctuate over time due to clogging, reduced adsorption capacity, or lapses in maintenance.

Carwash wastewater contains chemicals from exhaust soot, oil, and heavy metals from tires and brakes. Some of these chemicals are known to cause cancer, including lung and skin cancer through long-term exposure. Studies confirm they regularly show up in carwash runoff and can harm health if released untreated into streams and waterways. These cancer-causing chemicals are difficult to filter out of wastewater and place a heavy burden on municipal treatment plants.

Permitting and monitoring structure

The structure is being built on a levee, but is actually within the floodplain

The permitting process for small commercial operations can be relatively permissive in Ecuador. Ongoing oversight is limited. Wastewater monitoring is typically required about two times per year, with laboratory sampling scheduled in advance by the business.

This structure captures conditions during known testing windows rather than providing continuous or unannounced oversight. Discharges occurring outside these periods may not be detected, particularly if treatment performance varies seasonally or degrades between maintenance cycles. In sensitive watersheds, this monitoring gap is consequential.

Soil, floodplain, and subsurface transport considerations

The Rio Ayampe corridor includes low lying areas with a shallow water table and soils formed through river deposition. In coastal floodplain settings, permeable sediments can facilitate rapid infiltration of water and dissolved contaminants into shallow groundwater, with lateral transport back toward the river.

Seasonal flooding further increases vulnerability by mobilizing contaminants stored in soils or infrastructure and redistributing them downstream. Studies of Ecuadorian rivers, including Rio Ayampe, have documented the presence of heavy metals in sediments, indicating that the system already carries background contamination and that additional inputs increase cumulative risk.

Even in areas with finer textured or clay rich soils, contamination risk remains. While clays may slow vertical movement, dissolved surfactants and metals can persist, accumulate, and be transported through preferential flow paths or saturation during heavy rainfall. Comuna Ayampe's community well (~180 m/600 ft downstream, per my estimated observation) lies close to or within the hyporheic zone, where river water can mix with groundwater. Contaminants from the carwash could reach it via rapid subsurface exchange, bypassing surface detection. In the hyporheic zone, pollutants can flow laterally with groundwater following floodplain hydraulic gradients. A site-specific hydrogeological study should map flow paths, soil permeability, and travel times before considering a permit for this high-risk location. In all cases, downstream delivery to the estuary and surf zone remains a concern.

Water demand within a constrained basin

Carwashes are water intensive operations. A typical small facility uses approximately 50 to 300 liters of freshwater per vehicle. At 20 to 50 vehicles per day, this translates to roughly 1,000 to 15,000 liters withdrawn daily.

In Manabi, where agriculture accounts for most of the water use and communities already experience dry season shortages and flood related disruptions, this level of extraction is not trivial. The Rio Ayampe supports domestic use, irrigation, fisheries, and ecosystem function, with limited capacity to absorb new, non-essential commercial demand.

Implications for watershed management

Rio Ayampe estuary

From a watershed management perspective, siting a contaminant generating and water intensive activity immediately adjacent to a river increases reliance on treatment performance and intermittent monitoring rather than prevention. Once contaminants enter groundwater, river sediments, or estuarine environments, remediation is technically difficult, expensive, and often incomplete.

Public concern around this proposal reflects an understanding that in small, highly connected coastal watersheds, location decisions matter. Evaluating soil characteristics, flood dynamics, monitoring limitations, and downstream impacts is essential before approving land uses that introduce new contamination and extraction pressures.

Update January 17

A recent news report by Redacción La Fuente in Periodismo de Investigación provides a detailed look at the controversy and community response in Ayampe. The article describes how the construction adjacent to the river has prompted three formal complaints by residents, including one submitted to the Ministry of Environment, and raises questions about the legality of the land use and permitting process. The reporting underscores concerns that a project built so close to an ecological and community water source poses a risk to the river that supplies water and supports local livelihoods. You can read the full article by Redacción La Fuente here:

https://periodismodeinvestigacion.com/2026/01/16/ayampe-en-alerta-una-lavadora-de-autos-amenaza-el-rio/

References:

Review Technologies employed for carwash wastewater recovery. Journal of Cleaner Production. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652623008806

Emergency Appeal: Ecuador Floods and Environmental Contamination. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). https://go-api.ifrc.org/api/downloadfile/90851/MDREC027os

Análisis territorial de la cuenca del río Ayampe: una mirada desde la planificación ambiental. FLACSO Ecuador. https://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/items/7bc84bdc-3b07-4a99-ad0b-16a08866cbc2

Conservation threats and future prospects for the freshwater fishes of Ecuador. Journal of Fish Biology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jfb.14844

Territorial development, Intermediate government. Consejo Nacional de Gobiernos Provinciales (CONGOPE), Ecuador. https://www.congope.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/territorios-7-eng.pdf

The WASHReg Approach: Action Sheets. Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI). https://siwi.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/the-washreg-approach_action-sheets_updated-08-2023.pdf

Análisis de presencia de metales pesados en el río Ayampe. Universidad Estatal de Milagro (UNESUM), Ecuador. https://repositorio.unesum.edu.ec/handle/53000/6181

Khan, M. U., Malik, R. N., & Muhammad, S. (2018). Appraisement, source apportionment and health risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in vehicle-wash wastewater, Peshawar, Pakistan. Science of the Total Environment, 620, 1234-1244.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S004896971731570X

Bourke, S.A. et al. (2014). Characterisation of hyporheic exchange in a losing stream using radon-222. Journal of Hydrology, 519, 94-105. https://escholarship.org/content/qt1j52w92s/qt1j52w92s.pdf